- Published on

Mobile: The Future is Declarative

- Authors

- Name

- Lazar Nikolov

- @NikolovLazar

The mobile development ecosystem has always been very diverse, arguably more diverse than the web development ecosystem. While it seems like every day there are more frameworks and tools for web developers, a lot of them are built on top of JavaScript and implement similar patterns to each other. The mobile ecosystem, on the other hand, has a core set of languages that make the differences between mobile tools and frameworks much easier to identify.

Two of the leading native mobile platforms are native Android and iOS, both of which have had interesting innovations recently. With the introductions of Jetpack Compose and SwiftUI, developing native apps looks very similar to developing React Native or Flutter apps. Both React Native and Flutter have a declarative approach from the start, but with Android and iOS now joining the declarative bandwagon, we can see that the future of mobile development is declarative.

A little history

While React Native and Flutter have always taken a declarative approach, Android and iOS started completely different.

Android utilized (and still does) Views. Views are XML files where we define our user interfaces using widgets like Button, TextView, LinearLayout and where we assign IDs to those widgets. Those IDs are then used to reference widgets in our Java files where we develop the functionality and behavior. Here’s an example View file:

<LinearLayout

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent">

<TextView

android:id="@+id/text_view_id"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:text="@string/hello" />

</LinearLayout>

And we would create a reference to the widget like this:

public class MainActivity extends Activity {

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);

// Create a reference to the TextView using its ID

final TextView helloTextView = (TextView) findViewById(R.id.text_view_id);

// Change the TextView's text

helloTextView.setText(R.string.user_greeting);

}

}

iOS did have some declarative features, like Auto Layout, UIAppearance, the Objective-C @property declarations, KVC collection operators, and Combine, but it still required writing some level of imperative code.

For example, iOS had (and still has) Storyboards. Storyboards is a graphical tool we use to build our UIs. It is actually an XML file under the hood, but the developers almost never touch the XML code itself. Here’s how we added UI elements in our Storyboards, and created references and actions:

Being declarative

To refresh our memory, the imperative approach is when you provide step-by-step instructions until you achieve the desired UI. The declarative approach is when you describe how the final state of the desired UI should look.

Android’s new Jetpack Compose is written in Kotlin, which is a programming language as opposed to XML, which is a markup language. The previous XML View example would look something like this in Jetpack Compose:

class MainActivity: ComponentActivity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

// Start defining the UI

setContent {

BasicsCodelabTheme {

// Add a Row (alternative to LinearLayout)

Row(modifier = Modifier.fillMaxSize()) {

// Add a Text (alternative to TextView)

Text("Hello, Sentry!")

}

}

}

}

}

As you can see, building UIs with this approach requires a lot less code. And, since we stay in a programming language context, we can directly use variables and callbacks instead of creating references to widgets and attaching logic to those widgets. Any change in the values will trigger a recomposition (rerender), so our UI is always up to date.

iOS’s SwiftUI is pretty much the same, just built with Swift instead. The previous Storyboard example would look something like this in SwiftUI:

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

Button {

// handle onClick

} label: {

Text("Button")

}

}

}

Again, much less code. And we’re in a programming language, so we can directly define the Button’s label and provide an onClick callback without creating a reference.

One issue we stumbled upon when working with the imperative UIKit is activating constraints of a view before adding it to the view hierarchy:

let subview = UIView(frame: .zero)

subview.leadingAnchor.constraint(equalTo: view.leadingAnchor).isActive = true

// ^^^ it's going to crash on this line with the error:

//

// Unable to activate constraint with anchors *** because they have

// no common ancestor. Does the constraint or its anchors reference

// items in different view hierarchies? That's illegal.

view.addSubview(subview)

Swapping the subview.leadingAnchor.constraint(...) line with the view.addSubview(view) line will work without an error. Admittedly, it took me a while to understand what was going on when I first encountered this error, and I triggered this error a few more times until it became a muscle memory for me. But with the new declarative approach we’re not going to encounter this issue. (Muscle memory in coding is good, but it’s better to improve the developer experience).

This shift towards declarative in Android and iOS is a huge step towards better developer experience and faster development. Defining your UI in a declarative way using a programming language solves a lot of the pain points that Android and iOS developers have.

Here are some of the benefits of the declarative approach:

- Theming becomes easier and more dynamic.

- State Management feels natural and actually plays a crucial role in the new declarative approach.

- The composition approach allows us to compose our UI by nesting components, which is inferred from the nesting of the code’s block scope.

- Dynamic layouts and conditional rendering are now straightforward because we’re building our UIs with programming languages that have control structures and branching logic.

- It’s easier to grep through Swift/Kotlin code than through XML.

- We can more uniformly refactor our code using the same tools that apply to the rest of the programming language.

- The code diffs in PRs are easier to understand.

- Since our UI elements are built with actual data structures (i.e. functions, classes, structs) as opposed to markup language, we have the possibility of doing unit tests on our Views as well (not available for Jetpack Compose at the time of writing this blog post).

Of course, there are always some drawbacks to be aware of. It’s worth mentioning that both SwiftUI and Jetpack Compose are only 2-3 years old. A short research on their drawbacks will reveal the lack of documentation, smaller community, some performance issues (for example Android’s lazy columns), not all components from the previous frameworks are supported, and there are limitations when it comes to building more complex UIs. Though they are still evolving and improving, be mindful of the pain points if you decide to start working with them today.

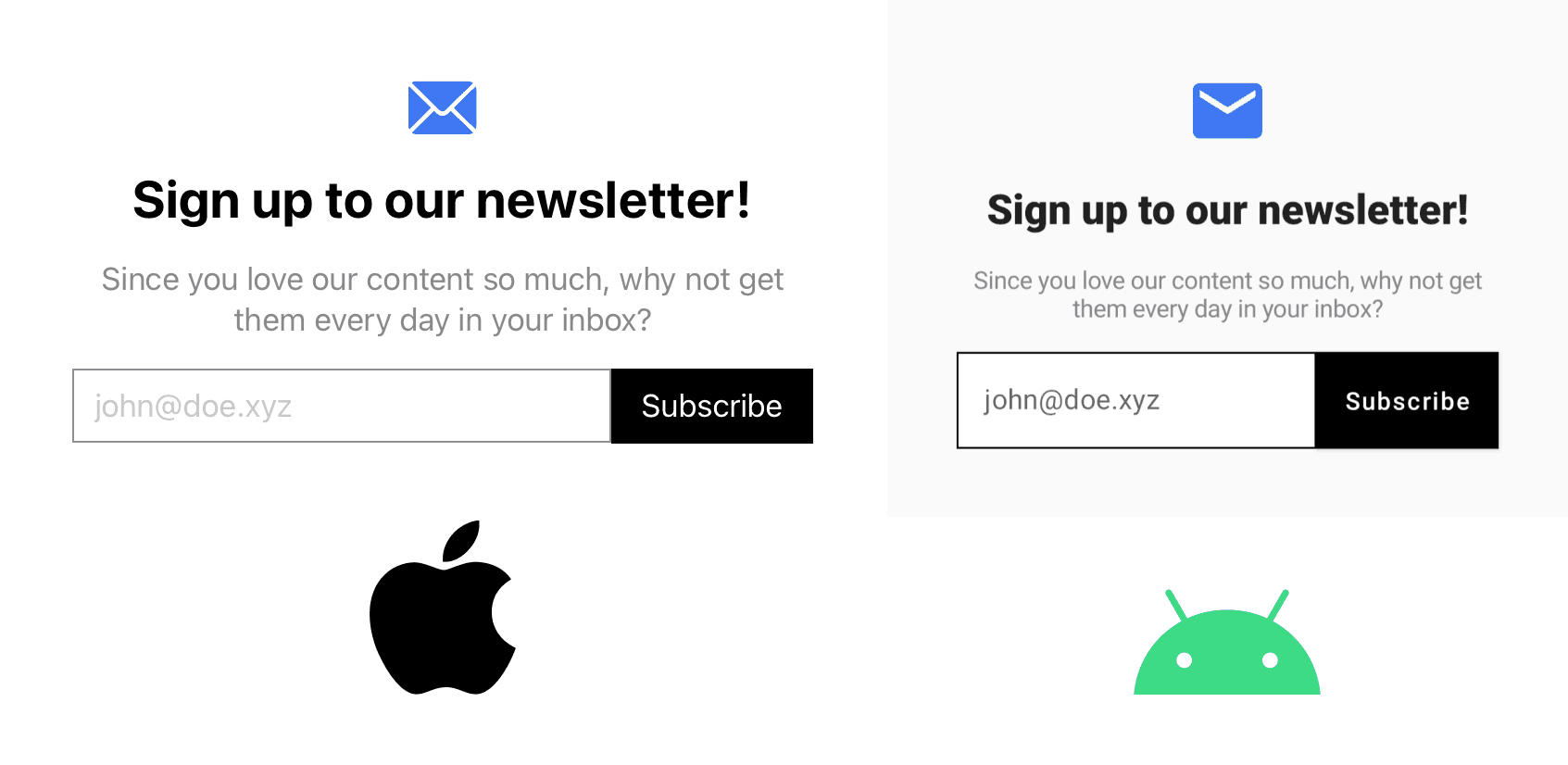

Example UI

Let’s look at how the same example UI is built in the declarative approach for both iOS and Android:

iOS (SwiftUI):

//: An example Modal UI built with SwiftUI

import SwiftUI

import PlaygroundSupport

struct ContentView: View {

@State private var emailAddress = ""

var body: some View {

VStack(spacing: 16) {

Image(systemName: "envelope.fill")

.font(.largeTitle).foregroundColor(.blue)

Text("Sign up to our newsletter!").font(.title).fontWeight(.bold)

Text("Since you love our content so much, why not get them every day in your inbox?")

.multilineTextAlignment(.center)

.foregroundColor(.secondary)

.frame(width: 400)

HStack(spacing: 0) {

TextField("john@doe.xyz", text: $emailAddress)

.frame(height: 40)

.padding(.leading, 12)

.border(.gray)

Button(action: {

// Handle onClick logic

}) {

Text("Subscribe")

.foregroundColor(.white)

}

.padding(.horizontal, 16)

.padding(.vertical, 10)

.background(.black)

}

.frame(width: 400)

}

.padding(40)

}

}

// Present the view controller in the Live View window

PlaygroundPage.current.setLiveView(ContentView())

Android (Jetpack Compose):

@Composable

fun Modal() {

Column(

horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally,

modifier = Modifier.padding(40.dp),

) {

Icon(

Icons.Filled.Email,

"icon",

tint = Color(52, 120, 246), // similar to the iOS one

modifier = Modifier.size(48.dp)

)

Text(

"Sign up to our newsletter!",

fontWeight = FontWeight.Black, fontSize = 24.sp,

modifier = Modifier.padding(top = 16.dp)

)

Text(

"Since you love our content so much, why not get them every day in your inbox?",

textAlign = TextAlign.Center,

color = Color.Gray,

fontSize = 14.sp,

modifier = Modifier.padding(top = 16.dp)

)

Row(

verticalAlignment = Alignment.CenterVertically,

modifier = Modifier

.padding(top = 16.dp)

.height(56.dp)

) {

TextField(

"",

onValueChange = {},

placeholder = { Text("john@doe.xyz") },

colors = TextFieldDefaults.textFieldColors(

backgroundColor = Color.White,

),

modifier = Modifier

.border(BorderStroke(1.dp, Color.Black))

.weight(1f)

.background(Color.White)

.fillMaxHeight()

)

Button(

onClick = { /* handle onClick logic */ },

colors = ButtonDefaults.buttonColors(

backgroundColor = Color.Black,

contentColor = Color.White,

),

contentPadding = PaddingValues(horizontal = 16.dp, vertical = 10.dp),

shape = RoundedCornerShape(0.dp),

modifier = Modifier.fillMaxHeight()

) {

Text("Subscribe")

}

}

}

}

Conclusion

The declarative approach of building UIs brings us a ton of benefits and eliminates a lot of the “pain points” we had in the imperative approach, but it also introduces new ones. Building UIs requires a lot less time with the declarative approach, and a lot less code. It’s also easier to achieve dynamic layouts and conditional rendering.

Since the native platforms are taking this approach, it also sets up the whole ecosystem for creating new frameworks on top of the native ones that will bring a lot more features and possibilities. It might be a bit early to call them “the industry standard” yet, but the mobile development world is about to get even more productive.